Where Are the Major Hurdles in India's ₹10,900 Cr Electric Bus Initiative?

By Ken Research’s Transport & Energy Sector Team | Expert insights into India’s EV policy execution challenges and electric mobility gaps.

In August 2023, the Indian government launched the PM e-Bus Sewa scheme, committing ₹10,900 crore to deploy 10,000 electric buses across 14 states and 4 Union Territories, including Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, and Chandigarh.

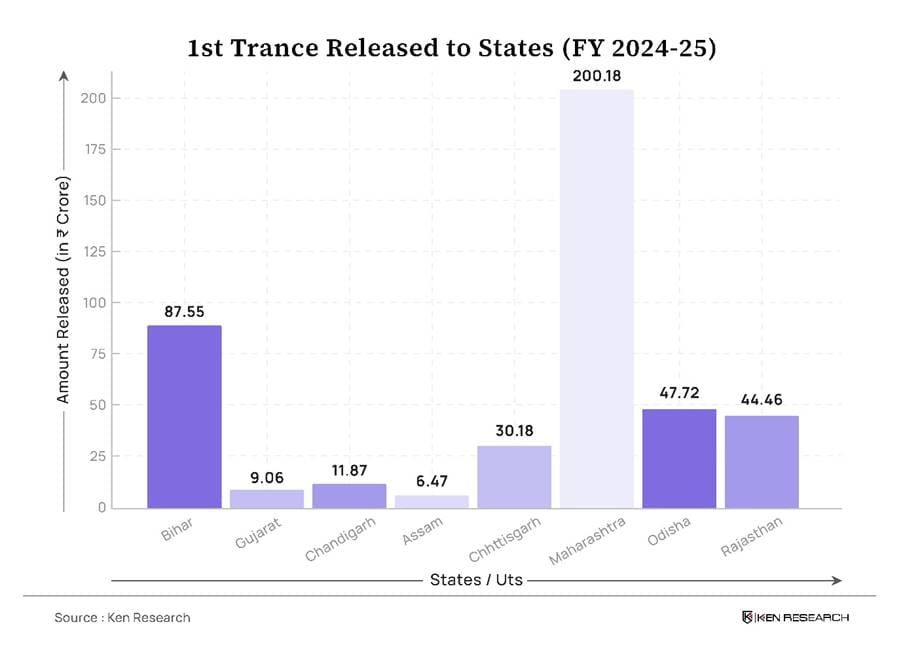

The initiative, part of the broader National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP), aimed to bridge environmental ambitions with urban mobility needs. It provided infrastructure grants amounting to ₹983.75 crore for depot electrification and power infrastructure upgrades across 66 cities, categorized under different urban. To support this, ₹437.50 crore was disbursed to 7 states and 1 Union Territory in the fiscal year 2024-25.

The model relied on a public-private partnership framework: municipalities planned the routes, while private operators owned, operated, and maintained the fleets. Operators were promised a ₹45 lakh subsidy per bus, designed to cover a significant portion of initial procurement costs, with the Centre subsidizing per-kilometer operational payments.

While promising on paper, the initiative has struggled to achieve meaningful deployment.

Why Private Operators Withdrew Early?

By early 2025, Convergence Energy Services Limited (CESL) had floated tenders for approximately 7,293 electric buses across 14 states and 4 Union Territories under the PM e-Bus Sewa scheme.

However, contracts had been awarded for only around 3,400 buses, and actual deployment remained minimal, with most cities still awaiting delivery due to infrastructure delays and long lead times in procurement execution.

Cities such as Kochi, Lucknow, and Bhopal saw repeated tender failures. In Kochi, for instance, only one bid was received in the first two rounds of tendering, falling short of technical and financial evaluation criteria.

CESL's aggregated tender for 3,132 buses floated in April 2024 also witnessed limited participation, even after multiple extensions.

Private operators increasingly withdrew, citing concerns over contract risk and viability.

How Contract Risks Undermined Viability?

Poor economic viability was at the heart of the disengagement. Municipal payment ceilings under schemes like FAME-I, while theoretically spanning ₹29–70/km, often fail to cover actual costs due to misaligned bid structures.

Realistic operational expenditures factoring in battery degradation, staff costs, and electricity tariffs (₹6.70–7.50/kWh as per CEA 2024 guidelines) push total costs to ₹77–80/km in initial years, creating an unsustainable gap.

Unaddressed long-term cost drivers:

- Battery replacement cycles

- Actual cost: ₹30–45 lakh per bus (300 kWh battery at ₹10,000–15,000/kWh)

- Replacement timeline: 8–12 years, with degradation rates of 2–3% annually

- Operational impact: Adds ₹0.09–0.15/km to costs over the bus's lifespan

- Emerging costs:

- Battery thermal management system repairs

- Specialized EV component replacements (inverters, motor controllers)

- Rising energy consumption from battery degradation (+5–10% over 8 years)

- Maintenance escalation costs linked to component wear

- Electricity tariffs varying between ₹6/kWh to ₹10/kWh depending on state-level regulations .

Infrastructure readiness was another major bottleneck. A February 2025 Ministry of Power report revealed that over 37% of designated cities lacked operational charging depots when tenders closed.

Additionally, while oil marketing companies had installed 4,523 EV charging stations by January 2025, only 251 were fully energized and compatible with heavy vehicle (bus-grade) fast chargers, which is insufficient to meet the scale needed for public transport electrification.

Historical subsidy delays under FAME-II (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles) had already weakened trust among operators, making them wary of participating without robust guarantees.

Attempting a Mid-Course Correction

Recognizing systemic risks, the government initiated corrective actions in late 2024.

- A Payment Security Mechanism (PSM), backed by ₹3,435 crore, was launched to guarantee operator payments even if municipalities defaulted (Ministry of Heavy Industries, 2024). The PSM operates through escrow accounts where payments are released automatically upon verified service delivery.

- Depot electrification efforts were expedited through new mandates from the Ministry of Power.

- The PM E-DRIVE Scheme allocates ₹4,391 crore for 14,028 e-buses over two years (2024–26), prioritizing nine megacities like Delhi and Mumbai, while CESL centralizes procurement to reduce costs through demand aggregation. Intercity routes are also supported to accelerate nationwide EV adoption.

These interventions yielded limited success. Companies like Adani Enterprises, JBM Auto, and EKA Mobility participated in CESL’s early 2023-2024 tender for 3,600 buses, which is now expanded to 4588 buses. Nevertheless, the number of bids per city remained below expectations.

"Policy adjustments help, but what private players want is a history of consistent contract execution, not just announcements," a senior NITI Aayog analyst noted at the March 2025 National Mobility Summit.

Delays Threaten India's EV and Urban Mobility Push

The slow deployment of e-buses has broader implications.

According to NITI Aayog projections under E-AMRIT, electric buses are critical to India achieving between 11 to 13 million annual EV sales by FY2030. Urban buses were expected to contribute 7–10% to total EV volumes, a figure now under threat.

If bus electrification stalls:

- The Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC) PLI Scheme has attracted significant investments aimed at achieving a projected battery production capacity of 50 GWh. However, there is a substantial risk of severe underutilization of this capacity.

- Urban local bodies, already fiscally constrained, will likely revert to diesel or CNG alternatives, compromising environmental targets set under India’s Updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted to the UNFCCC.

In essence, the private sector's hesitation could ripple across India's entire clean mobility value chain.

The Risk-Reward Gap That Still Holds Back E-Buses

The ₹10,900 crore PM e-Bus Sewa initiative was conceived as a public-private model for sustainable urban transport. However, it has inadvertently revealed deep systemic gaps between government ambition and market realities.

Even with improved funding and contractual frameworks, private operators continue to perceive major structural risks:

- Insufficient long-term guarantees on electricity pricing and battery replacement.

- Delayed municipal payments despite PSM mechanisms.

- Permit renewal uncertainties and inadequate force majeure coverage in Model Concession Agreements.

Unless these operational risk factors are fundamentally recalibrated, India's goal of electrifying public transport will remain vulnerable to stagnation.

The next two years of tendering and deployment will determine whether private capital can effectively align with public sustainability goals or whether electric buses will remain an unrealized dream.